My favourite albums and songs from May.

Albums

Honourable Mentions: Loom - Fear of Men, I Never Learn - Lykke Li, In Conflict - Owen Pallett

5. Luminous - The Horrors

Luminous may not have represented a drastic progression for The Horrors, but its lavished Dream-Pop and Indie-Rock harmonies are consistently great. Still as hazily wistful as ever, and possibly even more catchy.

4. Nicki Nack - Tune-Yards

Delightfully offbeat, wonderfully left-field, crisply executed Indie Pop. Exquisite production, a unique voice, and enough subtle idiosyncrasies for innumerable listens.

3. Casualties of Cool - Casualties of Cool

Folk has hardly been the traditional genre for translating Sci-Fi epics into musical narratives, but it's successful here. It's lyrically intelligent and emotive, but Aimee Dorval's vocals are possibly my favourite thing in music so far this year.

2. To Be Kind - Swans

In terms of actual quality, this is very probably the best album of the year so far. Devastatingly powerful, the very experience of listening to it is arguably traumatic, and unavoidably moving. While, personally, I find its lack of intimacy destabilising at times, I can attest that you will not have a more brutally profound listen, well, ever.

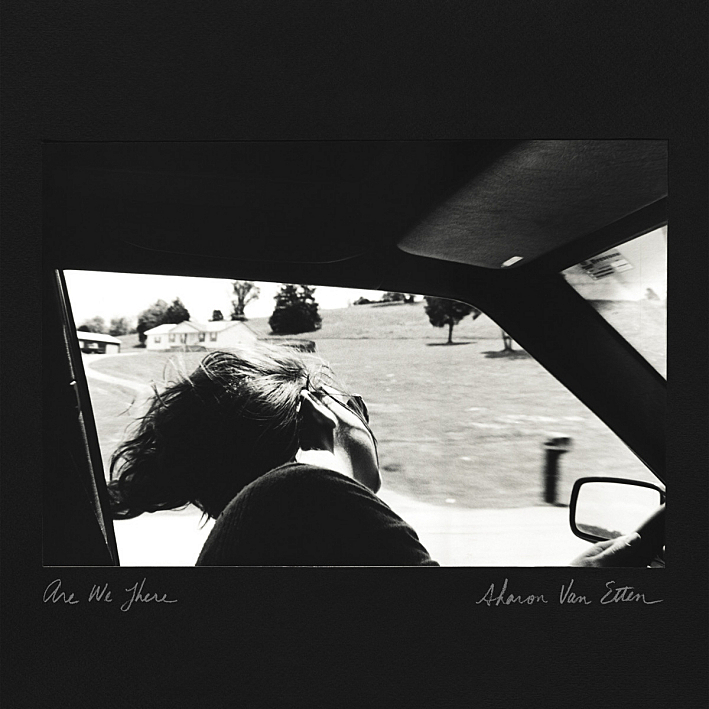

1. Are We There - Sharon Von Etten

If To Be Kind ignores intimacy, Are We There has it by the truckload. A break-up album this uncompromisingly vulnerable, this affectedly touching (almost to the point of debilitation), is astonishing. It is an externalisation of the most insular pain.

Songs

10. Real Thing - Tune-Yards

9. Until The Sun Explodes - The Pain of Being Pure at Heart

8. Goddess - Iggy Azalea

7. Our Love - Sharon Von Etten

6. So Now You Know - The Horrors

5. Just Like a Dream - Lykke Li

4. Flight - Casualties of Cool

3. The Riverbed - Owen Pallett

2. Water Fountain - Tune-Yards

1. Your Love is Killing Me - Sharon Von Etten

Publishing stuff about Film, TV, music, politics and whatever nonsense takes my fancy.

Thursday, 29 May 2014

Sunday, 25 May 2014

A Response To Michael Gove's GCSE English Reform

So Michael Gove has (more-or-less) axed non-British literature from the GCSE syllabus. I'm passed the anger stage of G.R.I.E.F. (Gove Ridiculous Idea in Education Fuckery). I've vented my futile outrage on Twitter and in conversation, and now I'm left with a feeling of guttural remorse and disenchantment. My despair is two-fold; not only is the innate inclusivity of literature being destabilised, but teachers are being deprived an avenue by which they can enthuse and motivate.

English Literature is just magnificent. A concurrent embellishment and critique of our entire socio-historical canon, it enthrals, it inspires, it teaches. Our cultural and pathological formation can be traced through the history of English Literature, and it is wonderful. But it is, by its very nature, limiting. Its assertion as a catalogue of ubiquitous values and narratives will be always be fundamentally incorrect as it is, not to its fault, unequivocally British. American literature conveys an entirely different perspective of society and humanity. It is, often, unconsciously driven by patriotism, or rural pastoralism, or existentialism, or post-colonialism; all these and more are often aspects of ourselves untapped, or represented completely separately, by our own literature. This is not confined to the English language. What about the Magic-Realism of the Americas? The Latin and Greek Epic Poetry? The Russian Romanticists and Naturalists? These are literatures culturally idiosyncratic but equally pertinent to the human condition. This reform deprives children not only of the chance to expound their imagination through the unfamiliar and progress their appreciation of different cultural discourses, but the opportunity to grow as people. The two examples of axed texts the media mention are Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird and John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men. One reaction to adolescence is a deep sense of insecurity and an ambivalent identity, which is often projected onto others through a series of predetermining, overarching judgements. Both To Kill a Mockingbird and Of Mice and Men are about accepting each other as we really are, pushing past our judgements and seeing our value; and more significantly, the dangers of ignoring these sentiments. Not only are these books important, they're important for those ages; 14-15, when you're monopolised by the turmoil of adolescence. Both these works, and many like them (The Catcher in the Rye, Robert Frost's poetry etc), I genuinely consider instrumental in my emotional and social maturity. They are terrifically written, but they also preach compassion, empathy, understanding, equality; values integral for our natural growth.

Secondly, the very purpose of education, particularly secondary education, is to inform and elucidate. Sure, in a neo-liberal society it's also to get good grades, a good degree, and a good job, but that's minute compared to our moral development. What is the point of English classes, as well as History, Geography, Physics, Maths, if it isn't to help us, and help others? Every lesson we've had contained the purpose of furthering our knowledge of ourselves and our external world. History is learning from the mistakes of the past. Human Geography is learning the system of social interactions which function our every relationship. Chemistry is learning the physical intricacies of our world and how we can utilise these to improve ourselves. Now imagine History teachers were informed they could no longer approach the Holocaust. Or Human Geography teachers weren't allowed to discuss the slums in Mumbai and Mexico City. Or Chemistry teachers were told they couldn't relate the details of cancer research in Philadelphia. All because they hadn't much relevance to Britishness. It's the same English teachers being told they can only do British texts. It is needlessly authoritarian, tragically preventive, and dangerously, bizarrely ignorant.

This will invariably come across as lecturous and self-aggrandising, but hopefully I translate the importance of unrestricted intellectual freedoms when exploring literature and its implications, and how such pathetic legislation undermines the essential point of education.

Tuesday, 20 May 2014

Catholicism and Dystopianism: The Correlation Between Morality and Destruction in Scorsese

‘”We

have a great war of spirit. We have a great revolution against culture. The

great depression is our lives. We have a spiritual depression.” (Chuck

Palahnuik, Fight Club)

Notable

examples from Martin Scorsese’s filmography illustrate Palahnuik’s ‘great

revolution against culture’ and consequent ‘spiritual depression’ in relation

to self-destruction. In Shutter Island,

Teddy Daniels attempts to unravel the mystery of Rachel Solando under the

facade of self-determination. However, unbeknownst to Teddy and the audience,

his narrative is invariably arbitrated by the psychiatric hospital’s staff;

furthermore, that he and his immediate society (the hospital) are conditioned

by self-destruction and madness. Similarly, in Goodfellas and Casino the

protagonists, and many of the main characters, believe that their lives of

excess and crime are, although illegal, not definably immoral as they are

upholding the traditional Italian, morally reputable values of family and

honour. In Scorsese’s moralistic universe, pain incited by immoral actions

obliges brief wealth and happiness before eventual, inevitable misery. Scorsese’s

gangster societies, embraced by amorality, are ultimately functioned by

self-destruction. This essay will first judge the protagonists of each film in

terms of their environmental context; and their appropriateness in representing

their society’s morbid relationship with self-destruction. Secondly I will

analyse each film’s respective social order, how their cultural tendency

towards amorality and hedonism habitually leads to self-destruction. Finally, I

will reach a conclusion about why Scorsese’s condemnation of spiritually

deprived excess is relevant to Palahnuik’s explanation of Fight Club.

Shutter Island’s destructive

universal politics can be seen as personified in its protagonist, the

delusional Andrew Laeddis, who will be referred to hereafter in this essay as

Teddy Daniels, Andrew’s synthetic identity. Teddy is given a ‘last chance’ by

Dr. Cawley to escape his delusion, by embarking on an artificial federal

investigation-which Teddy perceives as reality-to subversively achieve

realisation and acceptance that he killed his wife.

Scorsese

sticks unilaterally to Teddy throughout the film-even facial expressions and

dialogue Teddy does not experience are kept to a minimum-so that the viewer is

ignorant of Teddy’s secret as long as he is, and so they sympathise with him

intimately when this secret is revealed. Although the narrative is linear,

Scorsese routinely breaks up Teddy’s investigation with fragmented, but

elaborate, dreams, migraines and hallucinations; markedly the fire in his

building which allegedly killed his wife, and his experience of liberating a

Nazi concentration camp. Scorsese uses the sensationalist nature of these

scenes to infer Teddy’s suspicion of the hospital’s implication in Rachel’s

disappearance, and involvement with inhumane psychological experiments, while

concurrently supposing the unreliability of Teddy’s narration; the frequency

and intensity of his visions clearly demonstrate his mental instability even

before the epiphany. Teddy has been an article of misery most of his life, not

just at the island; he faced humanity’s vacuous violence in Dachau, was

afflicted by alcoholism, and was devastated by his wife’s insanity and

subsequent homicide of his three children. As the, purportedly real, Rachel

argues, ‘they’ll use your past trauma to explain why you’re crazy’. Scorsese’s

inference of doubt in this scene further complicates the already abstruse

depiction of Teddy’s psychology.

Equally,

Teddy is himself a violent man, ‘as violent as they come’ in fact, and

unconsciously seeking violence. Roger Ebert purports that ‘the hero is always

flawed’[1]. Arguably

then, he is destined for self-destruction because of who he intrinsically is.

In one of the film’s brief moments of pathos, the warden confronts Teddy by

telling him he cannot be controlled, that he needs an amoral authority because

there is no moral order. Furthermore, as Dr. Naehring comments, ‘wounds create

monsters’, suggesting that Teddy’s violent nature and traumatic past combine to

create someone integrally immoral ‘the [island’s] most dangerous patient’. Ultimately

the question of his punishment being justified is irrelevant, as Teddy suffers

the same fate irrespective of his culpability, signifying that misery and chaos

is permeating on Shutter Island. While Teddy’s morality remains ambiguous, his

universe’s certainly does not.

The

idea that Teddy is subject to Shutter Island’s [a]moral order, that he is not a

hero in his own separate narrative but an insignificant actor in a cynical universe,

an entirely distinct ontology from what he understands, underscores the

futility of his journey. The outcome of the roleplay determined Teddy would hurt,

regardless of whether he achieved realisation of his past actions and face a

lifetime of unendurable guilt, or relapse into delusion. Teddy’s investigation

is therefore not one of self-discovery, but self-destruction. In the final

scene Teddy says ‘This place makes me wonder; which would be worse-to live as a

monster, or die as a good man’. James Gilligan contends that this indicates he

feels too guilty to carry on living, that he ‘vicariously commit[s] suicide’[2].

Shutter Island differs

from Casino and Goodfellas; Teddy lives, and therefore suffers, in an amoral

universe within the confines of the narrative, rather than existing as an

immoral figure in a moralistic universe; he is predetermined to suffer, it is

not his choice. When the memory of Teddy’s wife tells him he needs to kill

Laeddis, ‘kill him dead’, it is Teddy’s subconscious provoking him to remove

the last shards of his real self. In rejecting Cawley’s ‘last chance’ offer of

coherent memory and identity, and George Noyce’s ultimatum of ‘digging the

truth or killing Laeddis’, Laeddis assumes his Teddy personality. Cawley

identifies acceptance as redemption, Laeddis identifies it as damnation; he

poignantly states ‘you can never take away all of a man’s memories’. By opting

for a lobotomy, a symbol clearly indicating death, he destroys his final sense

of person.

In

Goodfellas, Henry Hill’s plot follows

the traditional ‘Rise and Fall’ formula because he exists in a moralistic

universe where his dissolute actions

invoke injurious consequences. From the opening line of dialogue, ‘as far back

as I can remember, I’ve always wanted to be a gangster,’ the prevalence and

allure of the Mafia is immediately apparent. Scorsese uses quick cuts and

erratic camera movements to emphasise the transient thrill of such an excessive

reality for Henry. Equally, his employment of extended tracking shots-particularly

in the scene where the camera moves from outside the restaurant to Henry’s

table-articulate the intimate, familial bond shared by Henry and the Mafioso.

Some

characters, like Karen, find the Mafia’s ethical ambiguity difficult to accept,

but Henry’s assumption of amorality is instinctive and absolute, even from a

young age. For Henry gangster culture represents the realisation of the

American Dream, but for the objective, sensitised viewer ‘it's the American

dream gone completely mad and twisted’[3]. Henry

has wealth, power and a loving family; conversely he has betrayed Scorsese’s

concept of a cosmic morality to achieve this. As Billy Batts says, ‘good is

good,’ and Henry is not a good person.

Goodfellas differs

from Scorsese’s ‘Catholic’[4]

cinema, exemplified by Mean Streets,

because the protagonist (Henry) is not seeking redemption for his sins, or a

solution for a moral crisis. Emerson contends ‘the world Henry describes is one

in which there's no higher power taking moral inventory’[5]. He

is Palahnuik’s ‘spiritual depression’ personified. Charlie in Mean Streets attests that ‘You don't make up for your sins in church.

You do it in the streets. You do it at home,’ signifying that Henry’s fate is

inescapable. Henry’s decadence degrades him into adultery and drug

addiction, eventually leading to the collapse of his family and his testifying

against the Mafia. Goodfellas concludes

with Henry in the Witness Protection Programme, living in fear and isolation;

his own personal hell.

Similarly

to Henry in Goodfellas, Casino’s protagonist, the gambling

handicapper Sam Rothstein, is castigated for his adherence to mob culture’s

parochial amorality; because he exists in a narrative monopolised by Scorsese’s

Catholic values. When the viewer is introduced to Sam he is already an

established footsoldier in the Mafia, and in gang ethics, which raises an

interesting comparison with Henry’s moral development in Goodfellas’ opening, where he transgresses from naivety into

sociopathy. The audience will naturally find Sam a more difficult character to

relate to because the film does not chart his moralistic arc, which makes his

actions seem unequivocally wicked; for example, his violent employment of

‘cheater’s justice’ where he breaks the bones of anyone caught cheating. Not

only does he consider himself as above conventional morality but as above the

American legal system.

Moreover

Sam suffers Palahniuk’s spiritual depression. As an elapsed Jew, he is not

concerned by religious guilt or God’s omniscient judgement, and expects the

only power he answers to are his Mafia superiors. Sam eventually supersedes the

role of his absent God to become his own deity in his role as Tangiers Casino’s

manager, even to the point where he challenges the Mafia bosses; Emerson notes,

‘[he] aims for an infallible position where [he] can get away with anything in

the name of piling up cash’[6].

In Las Vegas, the Garden of Eden[7]

of amorality, Sam is a God. He notes, ‘here, I’m Mr. Rothstein’, offering a

figure of supreme authority.

Sam’s

towering arrogance, his genuine belief in his own omnipotence, is

characteristic of a self-destructive psychology. Self-destruction is the only

possible conclusion to the regime of reckless excess which Sam symbolises. His

God Complex inexorably leads to his downfall and the collapse of his hedonistic

paradise, as Scorsese ends with images of various casinos being demolished and

Sam’s nostalgic, unrepentant declaration, ‘the town will never be the same’.

The

narrative of each film’s protagonist represents their separate society’s

self-destructive ethics, but the protagonists are also circumstantial, trivial

actors in the context of their universe’s inclusive morality, or amorality.

The

moral landscape of Shutter Island is palpably

chaotic and destructive. Scorsese photographs the island as being hellish; it

is cut off from civilisation, and the cold barrenness of the scenery and storm

weather accentuates the unsettling confusion of the plot. Scorsese uses natural

grey light and jagged cinematography: scraggly rocks: crashing waves:

claustrophobic, dank hallways: and graveyards, to establish a sense of unease. Ominous

string and brass movements symbolise the volatility of the island and its

inhabitants. Scorsese’s utilisation of atmospheric music and imagery transforms

a conventional mystery thriller into psychological horror, with an overpowering

sense of fear and neurosis.

Along

with the obvious implications of paranoiac conspiracies and psychological

instability central to the narrative, various ideas contribute to the dread surrounding

the global horrors of post-modernism. There are references to controversial

psychosomatic experiments, genocide, Cold War suspicion, and nuclear weapons; one

patient claims ‘we hear things about the outside world, why would anyone want

to leave here?’ Alongside the use of German scientists in the hospital itself, these

elements allude to the evil inherent in man, as Teddy observes ‘after Dachau,

we’ve seen what human beings are capable of doing to each other’. The world was

undergoing a terrifyingly rapid transition following the 2nd World

War, and as another one of the patients insinuates, it would be a struggle for

anyone to adapt and progress in the real world, not just the criminally insane.

Ebert corroborates this; ‘everything is brought together into a disturbing

foreshadow of dreadful secrets’[8].

Even outside Teddy’s doomed investigation Shutter Island is home to a decaying

morality.

The

notion that Shutter Island suffers Palahnuik’s ‘spiritual depression’ is

evidenced by a lack of an orthodox God. As well as indifference a deeper moral

order of destruction mediates the narrative, as the warden comments ‘God loves

violence’, implying that there is a God, but not of the traditional

Judeo-Christian kind. There is no

Catholic morality, the only ethical code enforced is the methodical judicial

system, embodied by the warden and the board of directors, and the only

compassionate hospital official, Dr. Cawley, has little power over this amoral

ubiquity. Cawley claims he believes in ‘a moral fusion between law and order,

and clinical care’ and providing ‘calm’, a benevolent approach to psychiatric

treatment which directly contradicts the board’s irreverent attitude.

Significantly, his act of altruism, the only true act of empathy in the film-to

provide Teddy the intricate opportunity to escape his delusion-fails.

The

board want to tear out the soul, the individuality, of their patients by having

them drugged or lobotomised rather than treated therapeutically. The Warden

orchestrates a society of destructive apathy, a self-contained dystopia, where

vacuum of personality is preferred to madness. In lobotomising his patients, he

is systematically eradicating the spirituality of the island; ‘there is no

moral order at all’.

Where

Shutter Island corresponds with Goodfellas and Casino is in Scorsese’s implicit admonition of their collective

ethics. However, while his condemnation is categorical in his two gangster

films, where the protagonists are punished for refuting Catholic values and the

values of common decency, in Shutter

Island the moral figures are punished. The circumstances of universal

amorality determine Teddy’s suffering, not character actions, while Cawley and

psychologist/partner Sheehan fail in their attempt at compassionate treatment.

In condemning morally upright characters Scorsese highlights contemporary

America’s disdain for the mentally unhealthy, but more pertinently, the

deplorability of the island’s ethical politics and its indissoluble

relationship with self-destruction.

Scorsese’s

depiction of Mafia lifestyle in Goodfellas

has, being based on a true story, been praised for its authenticity, yet

Scorsese’s universe is not realistic but moralistic. David Chase refers to Goodfellas

as ‘The Koran’[9],

painting Scorsese’s film as a guidebook of gangster discourse and morality.

Certainly, it captures mob culture vividly.

Henry

Hill, and his immediate friends Jimmy and Tommy, live decadently and to excess.

These corresponding philosophies suggest a pervasive, cultural amorality and

spiritual void in Mafia society. Henry summarises this astutely, ‘when I was

broke, I’d go out and rob some more’. Considering most characters are from

Italian-Catholic backgrounds, a deep sense of Christian morality would

assumedly be instilled from a young age. However, these characters’ actions

prove to be the antithesis of Christian values; as well as drug abuse, they

murder, steal and commit adultery, breaking three of The Ten Commandments as an

active lifestyle. There is no spirituality to their lives despite their stanch

belief in the institution of family, both figurative and literal.

One

incongruous element of Goodfellas’ amoral

universe are the female characters; the gangster wives. While they do not

participate directly in their husbands’ criminality, the women are not helpless

spectators homogenised by a patriarchal environment. Karen enjoys her wealth

aware of her family’s source of income, and is fully capable of escaping that

life; which, arguably, renders her morally complicit. She concedes ‘I got to

admit the truth. It turned me on’. Indeed, Vinessa Erminio asserts that they

'all made certain moral compromises - looking the other way sometimes when the

men fool around, enjoying a good life paid for with blood money'[10].

The only truly innocent party in Goodfellas

is young children. Though gangsters perceive themselves as righteous

because of their familial love, substantiated by their self-idealisation as

bread winning, blue-collar workers, this is a misconception. Their families are

just as criminally and morally implicated as they are.

Each

character’s narrative seems to be regulated by an implicit, vengeful

Utilitarian power, and Utilitarian morality seems indivisibly linked with

self-destruction. Mill argues that Utilitarianism involves ‘giving to each what

they deserve[…] evil for evil[…] a proper object of that intensity of sentiment

which places the Just above the Expedient’[11]. In

this context the gangsters are attributed justice; they administer pain rather

than happiness, and are administered pain in return, ‘evil for evil’. For their temporal decadence they suffer moral

judgement. Tommy is killed because he murdered a ‘made’ man, a capital offence

in gangster ethics, while Jimmy was served a 20 years-to-life sentence. Paul

Cicero also died in prison. In a Utilitarian universe the gangsters’ amorality

and spiritual depravity means their downfall is inevitable; therefore, Goodfellas is self-destructive.

Casino’s portrayal

of gang culture ethics can be paralleled with Goodfellas’, especially since its setting is the metropolitan

embodiment of amorality, Las Vegas. While Sam, Nicky and Ginger individually

represent moral corruption and spiritual negligence, and indulge in the general

delusion of invincibility, in Las Vegas destructive apathy and deceit is

collective. The casinos try to cheat the public, a proposition the public

reciprocate. Nicky tortures, steals and murders, while Ginger and Lester

Diamond denote prostitution. Even the police are corrupt, as Commissioner Webb

targets the Tangiers after Sam fires his brother-in-law. Scorsese shows Las

Vegas to be quite literally Sin City. Sam describes it as a ‘morality car wash.

It does for us what Lourdes does for hunchbacks and cripples’. Evidently, the

denizens of Vegas are not seeking Charlie’s pathological concept of redemption,

but a vapid, temporary escape from their sins.

Furthermore

Mill’s definition of Utilitarianism is applicable since their escape is, after

all, only temporary. Las Vegas is an ephemeral Utopia in a moralistic universe,

and the characters’ sins will eventually damn them. Steven Sanders elaborates,

‘The Las Vegas setting provides the context for the social and psychological

realism that fills Casino and propels

the plot, whose moral centre lies in the predetermined ending’[12].

Surely, the fates of the protagonists are predetermined, and by distributing

only malignity to others they are repaid with only malignity. Nicky is killed

by his own gang, Ginger dies from a drug overdose, and Sam, like Henry, is

exiled to a life of reminiscing about the past. Assuming their fates are fixed

because of their self-indulgence, that the characters continue to exist in

depravity reveals Las Vegas to be an intrinsically self-destructive society.

In

conclusion, Palahnuik’s notion of the contemporary ‘spiritual depression’ and

the ‘self-destructive’ society is relevant to Scorsese’s filmography. In Shutter Island Teddy Daniels’ morality

remains ambiguous, yet he suffers because he is subject to a cruel,

uncompromising environment. By contrast, Henry in Goodfellas and Sam in Casino

are manifestly amoral and, although they enjoy fleeting success and happiness,

they are ultimately actors in a moralistic universe which punishes amorality.

All three films represent a culture either devoid of a God figure, or as

embracing an antipathetic God figure, therefore expressing Palahnuik’s

spiritual depression. Additionally, because the protagonists’ fates are,

arguably, predetermined, their insistence on intensifying their decadence-or

delusion in the case of Teddy-hints towards a self-destructive tendency. This

in turn can be seen to signify a wider social self-destructive psychology.

Filmography

Casino,

1995, Martin Scorsese. (USA: Universal Pictures)

Goodfellas,

1990, Martin Scorsese. (USA: Warner Bros.)

Mean Streets,

1973, Martin Scorsese. (USA: Warner Bros.)

Shutter Island,

2010, Martin Scorsese. (USA: Paramount Pictures)

Bibliography

Cox,

David; The Guardian, 2010. Shutter

Island’s Ending Explained. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2010/jul/29/shutter-island-ending

[Accessed 17th April 14]

Ebert,

Roger; Roger Ebert Reviews, 2010. Shutter

Island Review. [ONLINE] Avalaible at: http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/shutter-island-2010

[Accessed 17th April 14]

Emerson,

Jim; Roger Ebert.com, 2006. Goodfellas

& Badfellas: Scorsese and

Morality. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.rogerebert.com/scanners/goodfellas-and-badfellas-scorsese-and-morality

[Accessed 22nd April 2014]

Erminio,

Vinessa; nj.com. Soprano Women: Hear Them

Roar. [ONLINE] Available at: http://blog.nj.com/sopranosarchive/2000/01/soprano_women_hear_them_roar.html

[Accessed 19th April 2014]

Gabbard,

Glen. The psychology of the Sopranos: love, death, desire and betrayal

in America's favorite gangster family, 1st ed. (New York: Basic Books, 2002)

Mill, John Stuart. Utilitarianism, 3rd

ed. (London: Digireads.com, 2005)

Steven Sanders. No Safe Haven: Casino, Friendship

and Egoism in Mark Conard (Ed). The Philosophy of Martin Scorsese, 1st

ed. (Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2007)

Scorsese, Martin. Scorsese on Scorsese, 1st

ed. (London: Faber, 1989)

[1] Roger Ebert Reviews/Roger Ebert,

2010. Shutter Island Review. [ONLINE]

Avalaible at: http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/shutter-island-2010 [Accessed 17th April 14]

[2] The Guardian/David Cox. 2010. Shutter Island’s Ending Explained. [ONLINE]

Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2010/jul/29/shutter-island-ending [Accessed 17th April 14]

[3] Martin Scorsese. Scorsese on Scorsese, 1st ed.

(London: Faber, 1989) pp. 155

[4] Jim Emerson/Roger Ebert.com,

2006. Goodfellas & Badfellas: Scorsese and Morality. [ONLINE]

Available at: http://www.rogerebert.com/scanners/goodfellas-and-badfellas-scorsese-and-morality [Accessed 22nd April 2014]

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ebert. SIR.

[9] Glen Gabbard. The psychology

of the Sopranos : love, death, desire and betrayal in America's favorite

gangster family, 1st

ed. (New York: Basic Books, 2002) pp. 11

[10] Vinessa Erminio/nj.com. Soprano Women: Hear Them Roar. [ONLINE]

Available at: http://blog.nj.com/sopranosarchive/2000/01/soprano_women_hear_them_roar.html [Accessed 19th April 2014]

[11] John Stuart Mill. Utilitarianism, 3rd ed.

(London: Digireads.com, 2005) pp. 81

[12] Steven Sanders. No Safe Haven:

Casino, Friendship and Egoism in Mark Conard (Ed). The Philosophy of Martin Scorsese, 1st ed. (Kentucky:

University Press of Kentucky, 2007) pp. 8

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)